This book provides an introduction to the large number of different railways and locomotive types that were to be found across the expanse of the Indian subcontinent from the mid-nineteenth century through to the 1960s.

Published in February 2023 by Amberley Publishing and written by Colin Alexander and Alon Siton, this soft cover book measures around 23.4 cm x 16.5 cm, and has 96 pages and 180 illustrations.

It has a published price of £15.99 although Amberley Publishing currently has it on offer at £14.39, and at the time of writing, it can be obtained from Amazon for £12.17.

Trying to illustrate a railway network with over 70,000km of lines operated by well over 50 major companies and scores of minor ones is a great challenge in just 96 pages. However, the authors have achieved a reasonable result by adopting a mainly chronological approach, rather than covering the sub-continent on a railway-by-railway basis.

With many early photographs from the nineteenth century, some as far back as 1857, the book encompasses the time of the Raj from 1858 to 1947, as well as pre-dating the founding of the British Commonwealth in 1926. Some of the photographs show the stereotypes of those times, such as workers being overseen by a white-coated colonial supervisor.

The challenges of operating through the mountainous terrain of the Himalayan foothills are shown in several eye-opening photographs, while dedication to duty comes from a photograph of the signal box at Patna with its roof blown away by monsoon storms, but the signalman still working in his roofless cabin.

Whilst the photos have excellent captions, the bewildering number of different railways and unknown place names makes that information largely academic, although information about the subject locomotives or trains is useful. What would have been beneficial are some outline maps highlighting the major railways and locations.

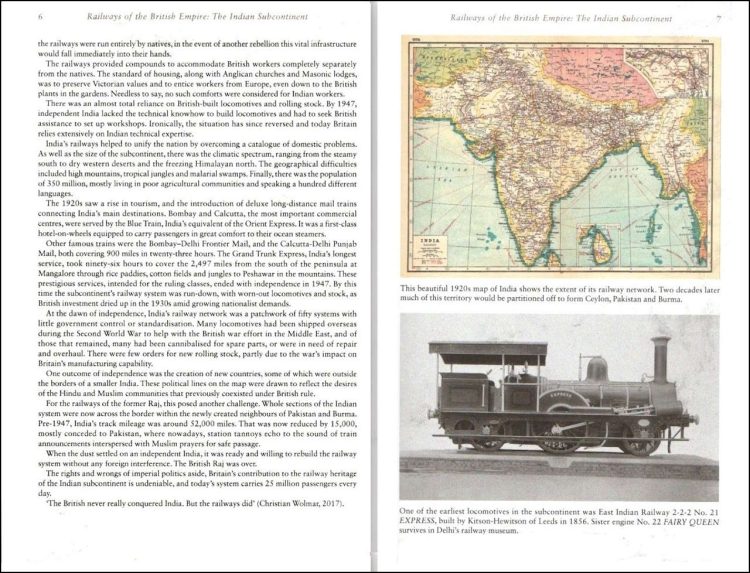

The large-scale map at the top right below is the book’s only map, despite the back cover stating that the book features contemporary maps. Whilst it shows the extent of the Indian subcontinent and its railways in the 1920s, it is far too small to be of any use. The photo at the bottom right is remarkable for being taken in 1856.

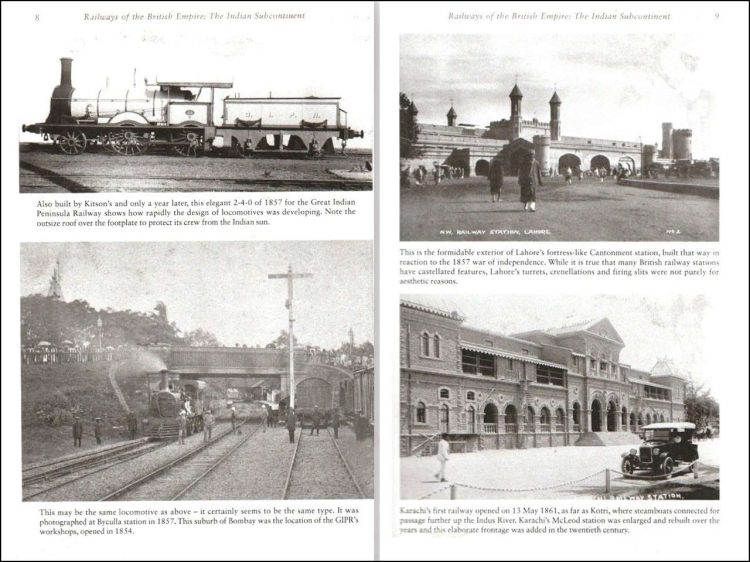

The tumultuous nature of the sub-continent becomes clear with many of the photos showing stations and structures bearing a resemblance to forts, with some even having slits in the walls for firing at attackers, such as Lahore’s station seen at the top right below.

There are also signs of ostentation in the design of some of the stations that, in some ways, resemble stately palaces rather than a place to catch trains, such as Karachi’s McLeod station at the bottom right, now renamed Karachi City Station. These two pages highlight the problem in arranging the book chronologically, as the train shown at the bottom right is in Bombay, which is 1,600km from Lahore in the top right photo.

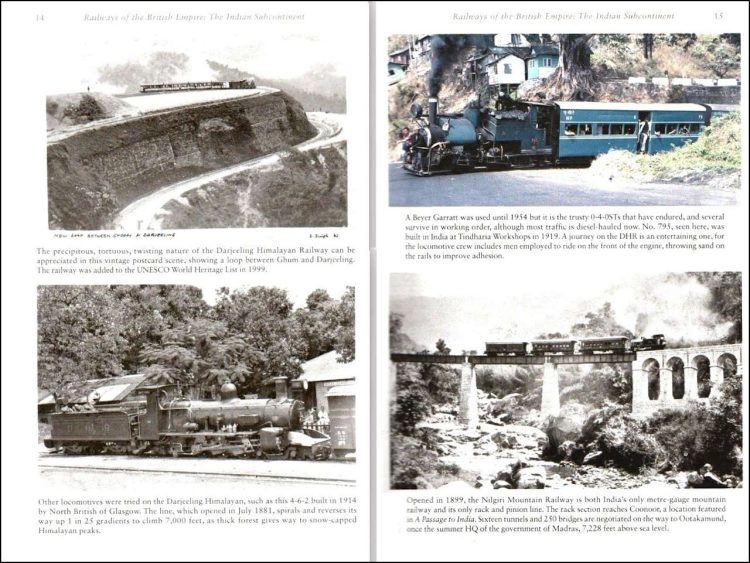

Probably the best-known of the subcontinent’s railways s the Darjeeling Himalayan Railway, as seen at the left and top right below, partly due to the precipitous nature of the line and its quaint locomotives. Although the photo at the bottom right shows another train on the Darjeeling Himalayan Railway, it is of the Nilgiri Mountain Railway, 2,500km to the south.

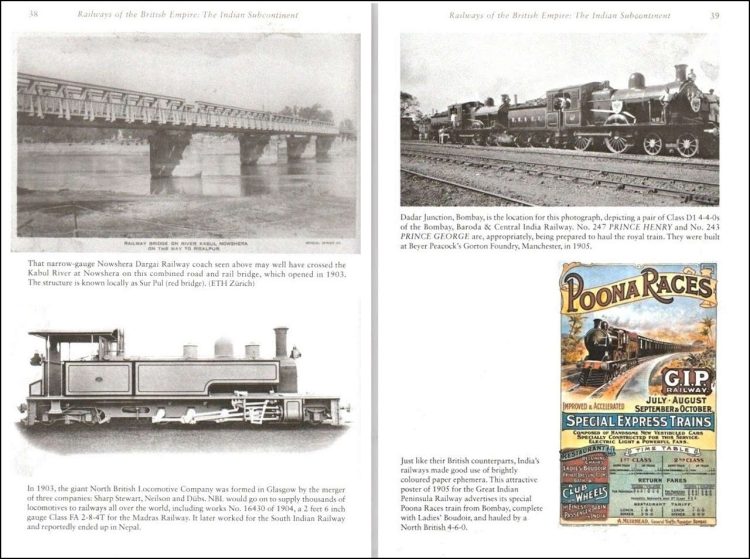

The problem of compiling a volume about railways of the Indian subcontinent without information about little-known places is highlighted by the photo at the top left, which shows a bridge on the Nowshera Dargai Railway at a place called Nowshera.

Searching the internet reveals that it is the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province of Pakistan, whereas if a few maps had been included in the book showing the various locations, it would have been a great help. The poster at the bottom right seems to echo the type of posters British railway companies published in the inter-war years, although I don’t recall seeing a British poster referring to a Ladies’ Boudoir, such as this one does.

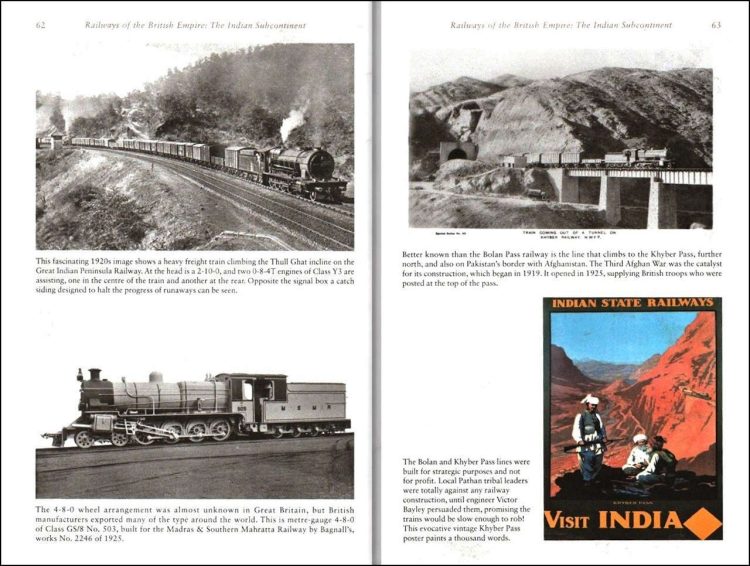

At first sight, the photos at the top left and top right below could have been taken on the same line, but the two locations are 1,600km apart. The train in the left-hand photo is interesting as it has two assisting engines, one in the centre of the train and a banker at the rear. They are required as the line has a continuous gradient of 1:37.

The two photos on the right-hand page perfectly complement each other, as the top photo shows a train climbing to the Khyber Pass, whilst the travel poster at the lower right shows armed tribesmen on the Khyber Pass, which somewhat detracts from the poster’s invitation to “Visit India”.

The book is available to purchase from Amazon and from Amberley Publishing.

We would like to thank Amberley Publishing for providing us with a copy of the book for review.

Responses