Published on 14th January 2022 and written by David Brandon and Martin Upham , this hardback book from publishers Pen & Sword measures around 23.4cm x 15.4 cm, is 280 pages long, and has a 16-page section of photographs and illustrations.

It has a published price of £25, although at the time of writing it can be obtained online from Pen & Sword for £17.50 and from Amazon for £18.99.

Part political biography and part railway history, this book examines the life of the man who appointed Doctor Richard Beeching to make recommendations on the future of British Railways. It describes how Ernest Marples was more than just the man responsible for instigating the infamous Beeching report, as he also inaugurated motorways and introduced significant regulations for motorists. Surprisingly, this is the first biography of Marples and shows how railway sentimentalism was no match for the growing power of the pro-road lobby.

To many railwaymen, Marples was always viewed as something of a villain. This book does nothing to dispel that opinion as it demonstrates the damage done to the railway was by a combination of road lobbyists, civil servants, and politicians.

The first six chapters cover Marples’ life and political career through housing, pensions, and Postmaster General, culminating in his promotion to Transport Minister in 1959. Although the content is sound, in some places it rambles with a discussion about events in the future before reverting to the subject in hand.

The next eight chapters explain why, by the late 1950s, road and rail transport both required change. Two chapters cover road transport up to 1939 and in the 1950s, two chapters cover the railways between the wars and from 1945 to 1955, and two chapters cover the Beeching Report.

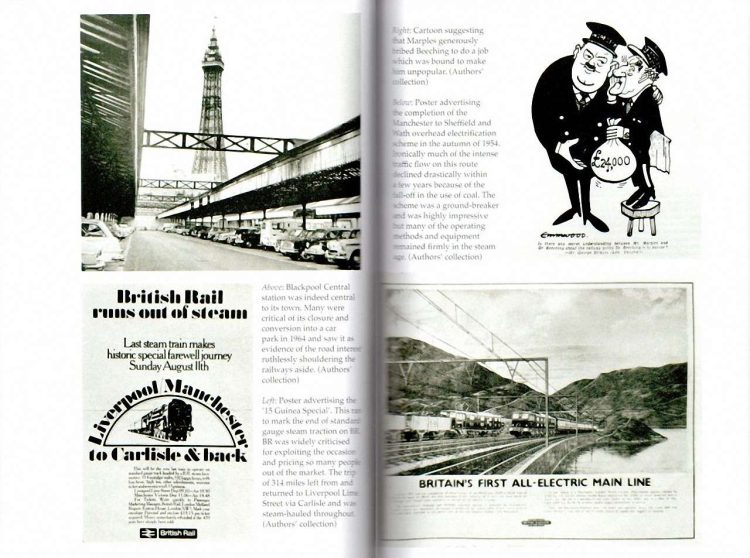

I found this to be the most interesting part of the book. It explains how Beeching’s proposals continued a series of closures that started many years before his appointment. Between 1950 and 1962, over 300 branch lines closed and 174,000 railway jobs were lost. It is clear that while large numbers of people had a sentimental attachment to the railways, this did not necessarily extend to using them.

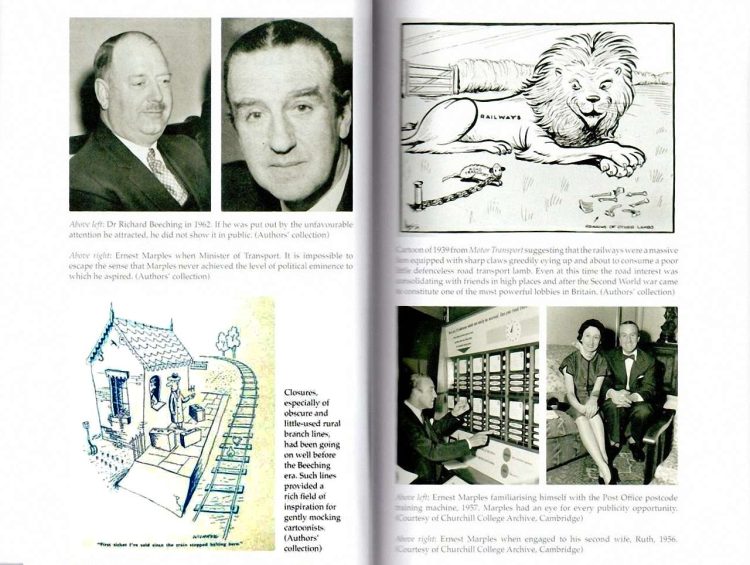

Publications have always carried cartoons lampooning the railways, and the ones on these pages are no different. The cartoon on the left highlights that closures had been going on long before the Beeching era, while the one on the right suggests that the railways were a greedy lion about to consume a poor little defenceless road transport lamb.

On the right below is another cartoon lampooning the railways, in which it suggests the Marples bribed Beeching to do a job that would make him unpopular.

There follows a chapter on Marples’ private life while he was at the Ministry of Transport, and a chapter on Barbara Castle, his successor as a Labour Minister of Transport. The last chapter describes how Marples, with the Conservatives in opposition, sought to investigate the impact that technology would have on British business, including making a special study of computers, although that was just a 23-day course put together for him by the three major British computer companies. It also covers Marples’ life, from his poor relationship with Ted Heath until his death in 1978.

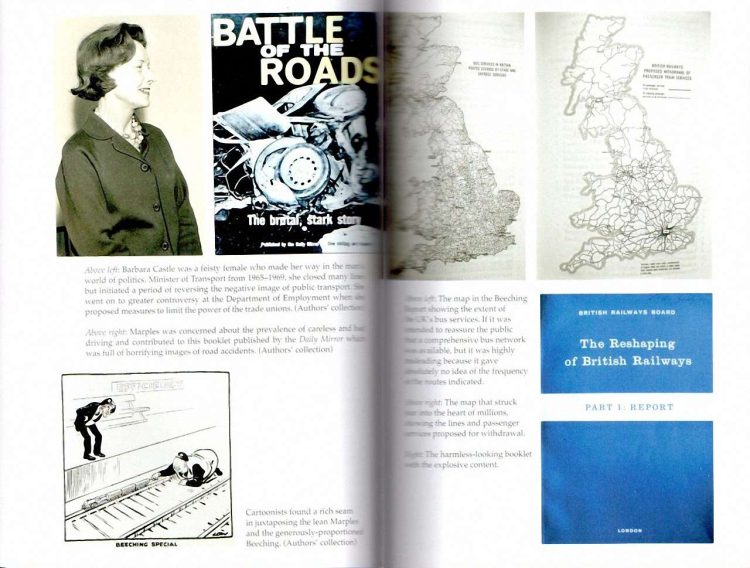

The below pages show Barbara Castle and the rather innocuous-looking cover of the Beeching report. The maps don’t show the before and after effects of the Beeching cuts on the railways, but are intended to reassure the public by highlighting Britain’s extensive bus network against the railway network once the Beeching Report had been implemented. Unfortunately, the bus map doesn’t give a true picture of what bus services will be available after Beeching, as it doesn’t discriminate between services running several times an hour with those that may run just once a week.

In summary, this book provides a balanced view of a man whose promise was never quite fulfilled. It should appeal to those interested in Britain’s railways and in mid-Twentieth Century British politics. For anyone who wants to understand why the British railway system was transformed in the 1960s, this book is highly recommended.

The book sets the scene of the transport conflicts at the time and gives a balanced view of Ernest Marples’ achievements, the obstacles he faced, his behaviour, and his determination to succeed. It is available to purchase from Amazon and from Pen & Sword.

We would like to thank Pen & Sword for providing RailAdvent with a copy of the book for review.

Responses

Remember many cars having stickers in their rear screens that said, “Marples jams are the best”. See now the lack of foresight by politicians of the time – we are now restoring old lines, building and opening new lines and stations.

I don’t know whether the book covers it, but Ernest Marples was of course part of the Marples family which owned a major civil engineering contractor – Marples Ridgeway. This contractor made a lot of money from motorway construction and this does leave one to wonder if this helped motivate Ernest Marples in his drive to close a lot of the rail network. Nowadays, this sort of conflict of interest in a Govt minister would be called out but in the 1960s it went largely unnoticed.