An experimental engine with a unique boiler, the London and North Eastern Railway’s W1 No.10000 forms the topic of this week’s Lost Class article.

LNER W1 ‘Hush Hush’ Class

The project’s main aim was to design an engine which was more efficient on coal than Gresley’s A1 class, currently in service. After considering various methods, Gresley decided on using a high-pressure water-tube boiler to produce steam for the locomotive he had set out to build.

Design and Construction

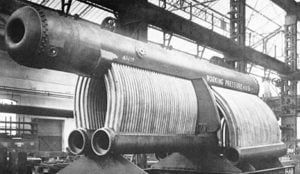

As the use of a high-pressure water-tube boiler for a locomotive was new ground, only used on a hand-full of American engines at the time, the design process had to be carefully thought out.

The project started when Gresley approached Yarrow and Company to help design and construct the boiler in 1924.

To ensure the design had the best chance of being a success, Gresley contacted a number of men, both within and without the LNER to provide advice. After four years of discussing, changing and adapting, the order for the four cylinders and parts of the boiler was made in July 1928.

The unique front end shape around the smokebox was created by using a wind tunnel in early 1929. By November 1929 No.10000 was completed at Darlington Works, ready for trials and test to start in December of the same year.

The basic dimensions for the W1 as built include: 4-6-4 wheel arrangement (coupled wheels – 6 foot (ft) 8 (in), leading and coupled wheels – 3ft 2in), Diagram 103 boiler (high-pressure water-tube boiler) pressed at 450 lbf/in2, four cylinders (high pressure – 12in diameter and 26in stroke, low pressure – 20in diameter and 26in stroke), total weight (including tender) came in at 166 long tons and tractive effort of 32,000.

Service in Original Form

The W1 ran for five months before being taken in for modifications. Then roughly three months in the works saw a number of changes occur, such as reducing the superheater element size and reducing blastpipe diameter to 4.75 inches. The engine was back in June 1930. Being an experimental design, 10000 spent the majority of its working life in original form undergoing repairs and modifications to various components.

Some issues were rectified after being repaired but others kept occurring on a number of occasions. 10000 never managed to match the performance of the A1s, this added with roughly 60% of its working life spent out of traffic lead to Gresley’s decision to rebuild the W1 in 1936.

Rebuilding

In August 1935 while 10000 was undergoing repairs, Gresley asked for all work to be halted on the engine. This was due to plans being drawn up to rebuilt the locomotive, which two months in October 1935, the W1 moved to Doncaster for rebuilding.

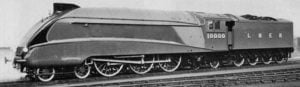

The rebuild followed the lines of the A4s, sharing a similar external appearance but a larger boiler beneath the casting to Diagram 111 (The water-tube high-pressure boiler was reused at Darlington Works for heating and ironically outlived the rebuilt engine).

Gresley’s 3 cylinders and motion layout were adapted but with 20in diameter cylinders over the 18.5in ones of the A4s. Although the frame was shortened, 10000 retained its 4-6-4 wheel arrangement which provided a large foot plate. The Kylchap blastpipe and chimney equipment was kept, which was fitted to other LNER Pacifics in later years. Complete and returning to traffic in November 1937, the new 10000 now had a tractive effort of 41,437 lbf.

Service in Rebuilt Form

In the rebuilt form, the valves fitted were seen as too small for the 20in diameter cylinders, which although hindered speed, didn’t affect the engine’s haulage ability. Although never matching the great achievements of the A4s, 10000 was still a good locomotive in rebuilt form.

Decline and Withdrawal

Despite suffering a derailment in 1955, which it was repaired afterwards, the W1 continued to work trains on the East Coast Mainline. Since the rebuild, only one boiler was made, which meant overhauls took longer complete than other engines.

The end for 60700, as it was numbered in BR days, came in Summer 1959 when the engine was withdrawn from traffic and later scrapped. The water-tube high-pressure boiler, as mentioned earlier, survived six years longer than the rebuilt 10000, being scrapped in 1965.

We hope you have enjoyed this week’s Lost Class and from all of the team at RailAdvent, we wish you a Merry Christmas and a Happy New Year.

We would also like to say thank you to all our readers for your continued support, we hope to see you all in 2019.

Where Next?

News Homepage

For the Latest Railway News

RailAdvent Shop

Framed Prints, DVD’s / Blu-Ray’s and more

LocoStop – The RailAdvent Community

Come and share your railway pictures

Responses

Gresley was aware that high-pressure marine boilers were more efficient power generators than their lower pressure railway counterparts, hence his approach to Yarrow. Two fundamental issues underlay the failure of this brave experiment. First, the limitations of the British loading gauge. The spatial constrictions were not compatible with optimum design. Second, the sheer battering a railway locomotive sustains in normal service, especially at high speeds, is absent in a marine environment. This insurmountable problem had a serious impact on a locomotive where tightness of steam joints and the need to stop air entering the boiler interior through breaches in the carapace were vital for economic performance. Try as they might, the engineers couldn’t overcome these issues. The rebuilt version, with its huge haulage capacity, was of great value during WW2, and thought was given to using it as a basis for future standard locomotive development on the LNER.

The firebox of the rebuilt W1 was about one foot longer than the A4 having the same footprint as the P2 and later A1. The frames did not need shortening and the space in the cab was not much different to the A4.

How about the boys from Darlington building the W1 (Hush Hush) Gresley 4 8 4 locomotive.

The tender was eventually paired to A4 60009 and made it into preservation. When No9 was overhauled in 1989 a new tender body was made for the original frames and continue in service today with 60009.

10000(60700) was 4-6-2-2 wheel arrangement and not 4-6-4